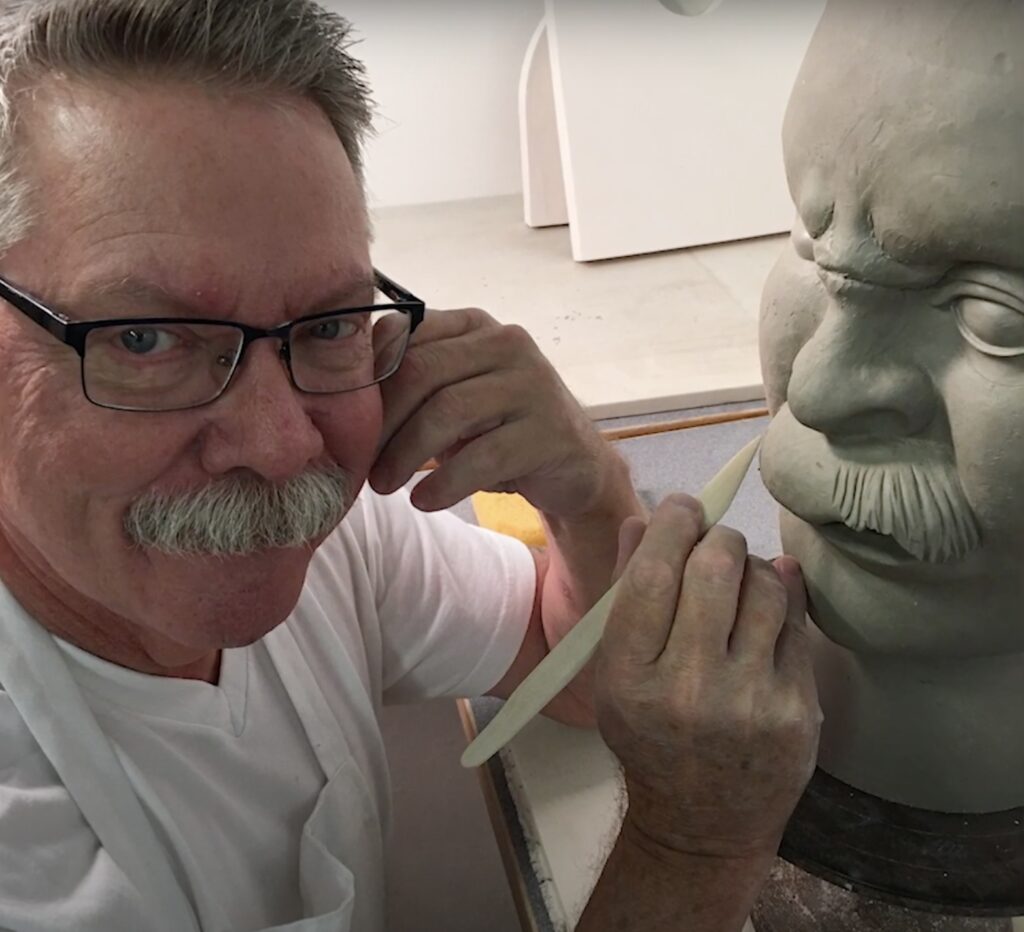

When I first arrived in Las Vegas to oversee the construction and development of permanent and temporary exhibitions for a new art facility I had designed for my dissertation, I made a point to meet with artistic, civic, cultural, educational, and nonprofit leaders within my new community. As the Executive Director and Curator of the venue, and a transplant from the San Francisco Bay Area, I was eager to meet like-minded individuals and organizations with the goal of generating creative alliances that would benefit the community at large. One of the first people I contacted was Mark Burns, Chair of the Art Department at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas (UNLV). I soon discovered that Mark was also an internationally acclaimed artist.

I greatly valued Mark’s insights as a colleague. Together, we collaborated on numerous projects to support an academic alliance between the university and the Erotic Heritage Museum (EHM). Mark’s dedication to his students was unmatched. He was not conventional by any means, despite being a serious artist and academic. His joie de vivre was truly inspirational.

A few years after I arrived, Mark decided to teach ceramics at Harvard University and devote more time to his art. As disappointed as I was to lose an ally and friend, I couldn’t help but be happy for him. I kept up with Mark’s career and achievements through the years, and it came as no surprise when he was awarded Fellowship of the prestigious American Craft Council. I was delighted to reconnect with him to reminisce about our past collaborations but more importantly, I was eager to learn his observations of academia and discover more about his art.

LH: When EHM first opened, I think it really blew people away.

MB: It did, it did.

LH: Most people did not know that I had been working on that project since 2002.

MB: Yeah. You wore many hats, as I remember.

LH: What was your impression of EHM?

MB: I think it was exactly what you said. It just blew everybody away. No one knew there was that much material that was being housed in one place, and Vegas seemed like a great place for it. And it certainly caused a stir, I think, in the entire community, because it addressed something that hadn’t been addressed before.

LH: What did it address that hadn’t been addressed before?

MB: The first time in there was an amazing experience. The subject matter you saw there – there’s always a smattering of erotica in student work – but what was in the museum was so blatant and undeniable. For many students, it was a touchstone that gave them permission to make the kind of art they wanted to make.

LH: Wow, that warms my heart.

MB: And it was a good thing, I mean, that we were really making openings. And the performances and the things that went on there were an eye-opener for people. I was always in favor of anything that could expand information the students were getting because a lot of times, the most important information doesn’t come out of academic minutiae, like at university. It was great to have that as a resource. Can’t tell you how many people I sent over there.

LH: I really tried to curate it as tastefully as possible and I designed it so you could explore at your own pace. You could explore exhibits that interested you, but by the end of it, you ultimately would have experienced the whole thing. What do you think the impact was to the community at large?

MB: I think that it was a really interesting place where what people thought about Vegas crossed over into something that’s more esoteric, that they might not have thought of erotica/porn as being art or sort of a cultural touchstone. That was a really important thing for the museum, be able to showcase the kind of material it contained. Also it took the fear of sex out of things for a lot of people.

LH: Mmm, I hadn’t thought about that.

MB: People who would never go into an adult bookstore could now go to the museum and get similar information because it had the word “museum” attached to it. That gave it a sort of legitimacy, a cultural weight. It allowed people to experience it without the stigma of going to, say, an adult bookstore.

LH: Accessibility?

MB: It gave it accessibility ,but it also gave it allowance. This is a museum, it has things in it that you might not expect to see in a museum. I think there was cultural weight behind it, so people could go and experience this thing without feeling like they had stooped to a level where they couldn’t tell anybody they had gone there, like going to an adult bookstore.

It had that same sort of energy to it. And “allowance” is a good word, “I’m allowed to go there, it’s okay for me to go there,” as opposed to, “I went someplace and can’t tell anybody I went there.”

LH: That’s a good point. When you were Chair of the Art Department at UNLV, you were really so warm and inviting and embraced the idea of collaborating. I was wondering if you could elaborate a bit more about the alliance made between the art department and the museum?

MB: That’s a really easy one. As I said before. I was all in favor of anything that could be bring a specific kind of experience to the student. Because really, to a 99.9 percentile, what was in the Erotic Heritage Museum was something that doesn’t normally get talked about in academic environments, even in art departments. The school needed to open an avenue for students to acknowledge the sort of material that was in the Erotic Heritage Museum, it’s part of a human experience. So,when students would drift over to the EHM… let me put it to you this way – the students needed all the input they could get about absolutely everything. So, that I think the work they were making wasn’t so academically produced, if that makes any sense. That’s an easy one. As I said before, I was all in favor of anything that could bring unique experiences to students. To be honest, what was in the EHM was material that typically isn’t discussed in academic settings, even in art departments. The museum opened up an avenue for students to acknowledge a part of the human experience. The students needed all the input they could get about everything. So, when students drifted over to the museum… they got something they wouldn’t have found on campus.

LH: Yes, it does.

MB: I think it was like this – there was a faculty meeting once, and I was not the Chair at the time, but we were each given a copy of Byte Magazine, B-Y-T-E, which is about computer stuff, so a ways back. And the Chair of the department had given us this magazine to look, but not for the reason I thought it was given to us. The Powerpuff Girls were on the cover. I said, “Oh, it’s the Powerpuff Girls,” and I named them – Bubbles, Buttercup, and what was the last one? Blossom. Some other faculty member said in a fairly condescending manner, “Oh, I guess that you would know what this is”. I replied, “Sure, I think you need to keep current with such things” because somebody at the table remarked that particular style of drawing was popping up in student work. I said, “We’re talking about what’s referred to as manga or anime.”

I said, “This is really important. The students are attracted to this and that you should know about it so that when you look at the work they’re doing. You will have a better understanding of why they might possibly be working in this way.” Vegas in its own way was, in many ways, to a lot of people, not quite as licentious as they thought it might be. So, the teaching that I was trying to do with the students, opening up to all the things that made the environment they were in useful. And of course, the Erotic Heritage Museum was there, to me just as useful as the Museum of Natural History, the Barrick Museum, all that kind of stuff. You needed to go over there and look at the EHM and process this information available. What you want to do with it is your business.

So, strangely enough, as the university was a cultural locus in Vegas at the time, it needed all the support it could get for things from other sources to branch out, to stay current. So EHM was a really unique thing when it came along. It raised a lot of eyebrows, but I think there’s nothing wrong with this at all. That the students really need the opportunity to make decisions based on information from myriad sources.

LH: The interaction, the collaboration, the alliance between us was rather short-lived for various reasons.

MB: Yeah, it was.

LH: But in that amount of time, could you see any sort of positive influence? I know I lectured a couple of times at the university and students often visited the place. Did you see any immediate positives from it?

MB: Yeah, I saw all sorts of positive things. I mean, it was one of the very first places I took my artist friends when they came into town to visit. They were just amazed that this thing existed over there, away from campus. And of course, it seemed very “Vegas” to them as they would work through the setups and we would talk a lot about things like the bathhouse panel paintings, etc. EHM was not just for gay and lesbian people, it was for everybody.

I loved going over there and being able to show work that might not be acceptable on campus. Some things I never showed at UNLV, I never had a solo show of my own there for various and sundry reasons. I think a lot of that was because people were afraid of the content. Perhaps the EHM represented what many thought was too lowbrow or “dirty”.

As for the students, I mean, with Anne Davis Mulford’s MFA exhibition, many of the responses she was given – I think that you would have to talk to her about that – some of the responses she got by students writing critiques for various classes were really unpleasant. They felt like they had been forced to look at this work and they didn’t want to look at it.

LH: Really?

MB: I remember one student review of the show said, “I don’t pay my tuition to look at lesbian art.”

LH: Wow.

MB: Also, such responses such as, “I think this is distasteful,” and all that. And so forth. There was a pretty straightlaced backlash sometimes at UNLV. As I’ve said numerous times now, I was always in favor of making sure that students knew that there were other opportunities to get information away from the university. That there were things out there that they might be able to connect to that they simply were not going to get on campus. You were so generous with your time and it was always great for the students to go over and visit. I don’t know. I couldn’t figure out why in some regards that it wasn’t…not everything in town was embraced, I think, the way it should have been. Don’t you think?

LH: Oh, yeah.

MB: But the students, they got a lot out of it. And so the thing about it was, when I had you into the BFA class to talk about what was in your museum was immeasurably important for them. You were a real person standing there who was wearing a number of hats at the time. They got a lot out of that. So, you have to draw from the community because the universities are usually pretty cloistered for bringing people in, different points of view. It was nothing but good for the students though, yeah.

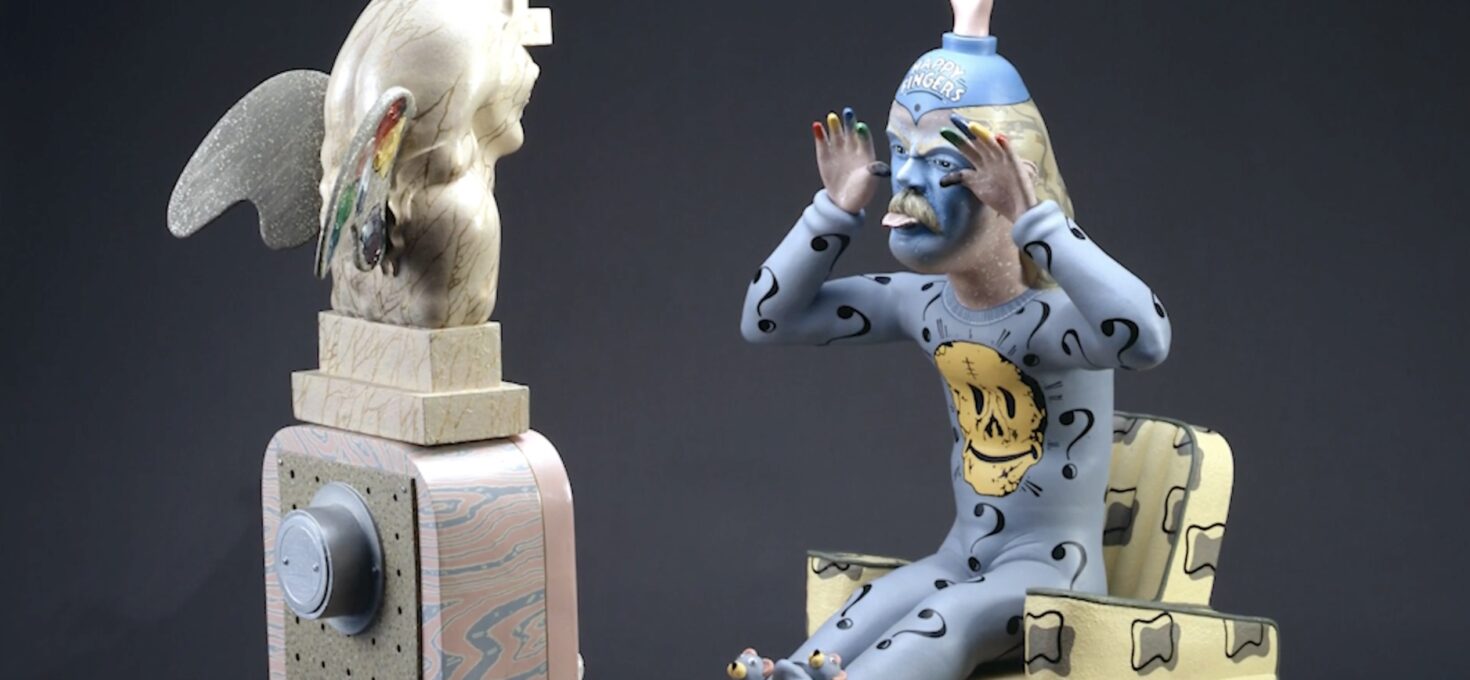

LH: Wonderful. Well, I’m going to shift gears then to about you exhibiting as an artist. If you can explain to me the name of the piece, the medium, and what the piece actually meant to you, I’d love to hear this in your own words. It was a fantastic piece.

MB: The name of that piece was Sinister Urge, which is the title of an Ed Wood movie. I told somebody that I could build a feminist piece, and I did. I’m here to…let’s talk about mixing it up a little bit. If you remember, it was all pink.

The piece was about female’s day and night activities, very tongue in cheek. I wanted to do this because there was some solidarity there with the other female artists I was working with and it was a challenge. The piece was all made out of clay.I did it in the ceramic department in my office studio space.

There will always be a group of people who think ceramics should basically be pottery. So, a lot of what was coming out of the ceramic department over there at UNLV, because I ran it, it raised a lot of eyebrows. I was trying to form a closer alliance with sculpture as opposed to craft. I closed the pot shop down because there was not a whole lot of interest in it at the time. I did get into some hot water for doing that. There wasn’t anybody in town I could get who could teach it effectively, then all that stuff seemed to backfire. Of course, when they made me the chair, things got even worse because you can’t serve two masters let alone three.

The thing I built started falling apart. I wasn’t getting my studio work done because I was doing the business of the university. Then came the terrible years of… Well, I won’t go into who it was, but there was such unrest because of the financial trouble the school soon got itself in. But yeah, so that piece – Sinister Urge, which belongs to a good friend of mine, was a way for me to sort of start crossing over, to practice using particular kind of imagery and, again, a kind of solidarity.

LH: So, how would you describe yourself as an artist?

MB: Other than a hot mess.

LH: Yeah. [Laughter]

MB: I describe myself as a storyteller. Well, I try to physically fabricate versions of stories, personal things, my stories are tied up with other elements – pop culture, religion, music, literature. I think a lot of people there never really understood the work that I was doing because it was pretty complex and really esoteric images. Like, my version of the Judgment of Paris, an all-gay version. I did have a piece to show in the faculty show that had a Tom of Finland painting on one side and a great china painting of a Crisco lable on the back. The side with the Tom of Finland erotica kept being turned around to face a wall because some people found it offensive.

LH: Wow.

MB: My storytelling, sometimes it’s really blatant, sometimes much more coded. There’s an entertainment factor always in my work, but I have been and always will be a storyteller. The clay material just allowed me to do that because there’s a long history of such work.

LH: I know that you’ve exhibited at some incredible places in the country. I, honestly, was completely honored that you would exhibit at the museum.

MB: Who wouldn’t? We had a great time, it was really a lot of fun. You had Anne Davis Mulford, you had KD Matheson. You had some really terrific people out of the community there. That was the only time all those people sort of came together. That was great. I wouldn’t have passed that up for anything.

LH: Thanks. Was there a favorite exhibit that you liked at the museum? Was there something that you always would gravitate to? Because, I mean, there was 24,000 square feet altogether. 17,000 square feet was permanent exhibits, but the other 7,000 square feet was always changing.

MB: Yes, but this is going to sound like a blanket, but I liked them all.

LH: Okay. [Laughter] I’m glad you liked it all.

MB: And really, I think because it was not just the novelty aspect of showing at EHM, it was how well put together the shows were. It was a real chance to see other artists from the city, from the community, and that was a really wonderful thing. But I also really liked the LGBTQ panel that you asked me to be on with Suzanne Shifflett and others from the community.

And all of that. That was a really wonderful experience. And it was great because, really, it was a chance for me to speak in public, because by that time, I had become this kind of villain. People believed I fired David Hickey but I didn’t.

LH: You didn’t fire David Hickey.

MB: There’s that infamous page I did with the artist community book project “Drunk”. My page, which was just a parody of the last page in 50s comics, got me in all sorts of trouble. Without going into all that nonsense again, people just saw my effort as being an attack on our local celebrity genius.

LH: Ridiculous.

MB: It was. But I don’t regret doing it at all. That page parody had the coupon you could cut out and send to the Gibberish Arts School to get an art degree by drawing a turtle. Get a degree through the mail!

You hosted some really interesting after-hours things there at EHM.

LH: Yes, I did. [Laughter]

MB: Yes. I liked the bondage affair. That one was very interesting. Everyone learned to tie better knots.

LH: [Laughter] So, let’s see. As far as being an artist, why is it important for you to want to create provocative art? Is it just something that comes naturally or…?

MB: Yeah, it simply comes natural to me because I think about the things I like to make, especially in clay. It took a long time for people to figure out what I was doing. For me, in many ways, art is another kind of entertainment.

And that’s just based on my own queer identity and being raised in a really repressed era and living in the part of the country I was in. Making things was an outlet for me. I was a kid who was always raised on rural drive-ins surrounded by cornfields, so all of the work I did, I mean, usually it was kind of a yearning for something else, something that didn’t feel so restrictive.

Plus, I like to have a good time.

Shock value has its purposes. But I was, like I say… I think as years gone by, much of the work I did has started to become regarded in some other way. Know what I mean? It’s not every hot mess that gets to be a fellow of the American Craft Council. Two years ago, I got inducted into the ACC, that’s kind of like the Oscar for people who work with craft materials.

But a lot of that was because I was stressing out. Part of the thing was I just kept right on making stuff that went in and out of fashion. As an artist, you simply make. I guess. I like to make things. Making things, sometimes I’m not sure exactly what they are, but it’s a way to keep your mind busy.

LH: You mentioned that you were recently inducted into the American Craft Council?

MB: Yes, I became a fellow with the Council.

LH: So, pottery and ceramics is considered more crafts and not actual sculptural?

MB: Well, that was the bugaboo for many years, it was simply considered a craft.

Ceramics had never crossed over into the art world until early in the ’70s, when I went to graduate school. People stopped making pottery and started making other kinds of objects.

They started making sculpture.

I will tell you a secret, Laura. In many ways, I never called myself a ceramist. I was a person who made things. Because I realized early on ceramics, the material itself, could not produce some of the things I wanted it to, that I had to go and get other material to incorporate into it to get the effect I wanted.

There was a time when I was not thought well of. I was polychroming and not glazing, because I just felt that the illustrator in me liked the paint better. It was not as unpredictable as glaze. Now, it’s pretty much open, anybody can do whatever they want with it. But there was a time when I was also sort of depressed. It was difficult to navigate when I started as an artist because I was gay.

That was not something that you went around advertising. People knew but to make explicit work to address that queerness, well, you didn’t see very much of it. A couple of years ago, I got dubbed the Fairy Godfather of American Queer Ceramics.

LH: [Laughter] Oh my!

MB: Which I thought was really funny.

LH: I love it. [Laughter]

MB: Yeah, the woman that did the catalog for a show I was involved in titled “Sexual Politics” called me and said, “Do you mind if I call you that?” I said, “God, no. People have been calling me that for years.”

The Fairy Godfather of American Queer Ceramics.

LH: [Laughter] I love it, I love it, I love it.

MB: There was a few came before me but I was much more blatant about it, let’s put it that way.

LH: This was wonderful. We need to chat more often!

MB: Yes, we do!