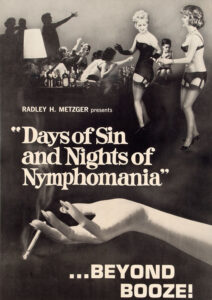

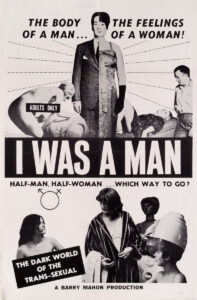

The story behind adult movie posters in the United States is truly a fascinating tale. These posters represent a time when federal, state and local obscenity laws inevitably created a unique art genre: Erotic American Folk Art and Cinema.

I created the Theater of the Moving Image, a permanent exhibition, and also the rotating exhibit, Poster Art of Erotic Cinema, to present films from 191o to early 1990s. Included in the exhibition were film reels (Super 8, 16mm, 35mm) featuring a variety of sexual orientations, movie posters (aka one sheets) and ephemera, movie scripts, and vintage film equipment. The permanent exhibition changed often with new films and objects to present a comprehensive view of this genre of American cinema, as well as to provide the viewer a context of cultural norms from era which these films were made. Two theaters were created and several monitors utilized throughout the facility so that patrons could sit, watch and discuss exhibited works.

I created the Theater of the Moving Image, a permanent exhibition, and also the rotating exhibit, Poster Art of Erotic Cinema, to present films from 191o to early 1990s. Included in the exhibition were film reels (Super 8, 16mm, 35mm) featuring a variety of sexual orientations, movie posters (aka one sheets) and ephemera, movie scripts, and vintage film equipment. The permanent exhibition changed often with new films and objects to present a comprehensive view of this genre of American cinema, as well as to provide the viewer a context of cultural norms from era which these films were made. Two theaters were created and several monitors utilized throughout the facility so that patrons could sit, watch and discuss exhibited works.

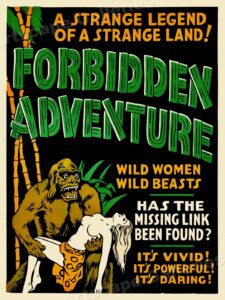

As soon as the first motion picture camera was invented in 1891, capturing the human form in every way imaginable was inevitable. The silent films of the early 1900s unleashed an unbridled voyeurism, nurtured imagination, and provided remedial, if not biased, sex education. If we look back at the era of Victorianism when the first nudie films were made, it was publicly scandalous for a woman to expose her clothed ankle in public! In fact, the seats of female sitting chairs were pitched at a downward angle so that when a woman sat in her gender assigned chair, her clothing followed suit and would cover her ankles. If she sat in a man’s chair, her skirt would rise up and expose her clothed ankles to wondering eyes. Oh, the indecency! The Puritan norms of the day were stifling for women; however, for men, it was definitely a man’s worlds and men were not as restricted. The men’s social clubs of that era allowed and supported intellectual enlightenment for their gender. It was not a stretch for men to see nudie films in such places. These films were also referred to as stag films. The opportunity to see a woman removing her many articles of clothing, proudly parade her nude body or perform a sexual act in front of a camera was was mind blowing. Being that women were not equal to men, a woman was forbidden to see such films as their brains and physical constitutions could not handle such stimulation. Females in the 20s and 30s pushed social boundaries and were certainly more brazen with regard to their sexual desires. I like to think that maybe, somehow women got access to some of these stag films. They certainly may have seen footage, but the advent of the vibrator in the early 1900s provided a predestined outcome that would collide with movie magic to create the money shot.

Fast forward to the 40s and 50s when film technology advanced considerably and accessibility to own a movie camera became a Normal Rockwell-inspired reality. By the 60s, Kodak manufactured the Super 8 camera for amateur filmmakers. Now any American household could produce a film. Imaginations were yet again unleashed. It was a synergistic moment in time: the natural evolution of filmmaking due to mass production and access (movie cameras) and opportunity (filmmaker/model) combined with a tsunami called The Sexual Revolution (free love/the pill/bacchanalian experimentation) that launched the existence of sexploitation films.

Fast forward to the 40s and 50s when film technology advanced considerably and accessibility to own a movie camera became a Normal Rockwell-inspired reality. By the 60s, Kodak manufactured the Super 8 camera for amateur filmmakers. Now any American household could produce a film. Imaginations were yet again unleashed. It was a synergistic moment in time: the natural evolution of filmmaking due to mass production and access (movie cameras) and opportunity (filmmaker/model) combined with a tsunami called The Sexual Revolution (free love/the pill/bacchanalian experimentation) that launched the existence of sexploitation films.

As sexploitation films became more and more popular, an underground market began to emerge. It was not long before persons realized that serious money could be made from creating and distributing such films. Of course, it was illegal to sell, mail or cross state borders with such material. These films were deemed obscene and the distribution of such films were considered a federal offense. Regardless, the smut prevailed and demand continued to grow. Authorities could not squash this emerging film industry. They certainly could not stop contraband flowing into the hands of consumers. By the late 60s, adult movie theaters began to spring up across the country as it was now possible to watch adult film at public venues. The sexual revolution changed social norms so that the film industry was thriving; however, producing and distributing films meant jail time for many. For those many, the sacrifice was worth it.

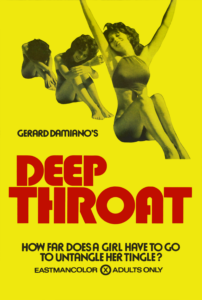

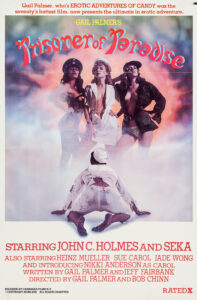

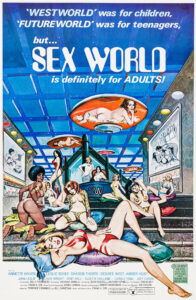

From the shadows and into the light, the adult film industry in the 70s really came into its own. Movies were now big film productions with 35mm cameras, film crews, and all the bells and whistles of a mainstream Hollywood motion picture. Locations were exotic and screenplays Oscar-worthy. Despite adult films becoming mainstream, local and federal authorities were always trying to shut productions down. It would be typical for actors, directors, producers and an entire film entourage to outwit, outrun and outmaneuver police and vice squads due to the federal, state and local obscenity laws. It was not unusual to have an attorney on retainer to help bail everyone out of jail for breaking obscenity laws only to be incarcerated again and again for the same crime. Being a producer, director or actor of an adult film held both glamour and mystique. In fact, these individuals became household names and words from adult movie sets became part of our venacular. Can you say, Fluffer?

From the shadows and into the light, the adult film industry in the 70s really came into its own. Movies were now big film productions with 35mm cameras, film crews, and all the bells and whistles of a mainstream Hollywood motion picture. Locations were exotic and screenplays Oscar-worthy. Despite adult films becoming mainstream, local and federal authorities were always trying to shut productions down. It would be typical for actors, directors, producers and an entire film entourage to outwit, outrun and outmaneuver police and vice squads due to the federal, state and local obscenity laws. It was not unusual to have an attorney on retainer to help bail everyone out of jail for breaking obscenity laws only to be incarcerated again and again for the same crime. Being a producer, director or actor of an adult film held both glamour and mystique. In fact, these individuals became household names and words from adult movie sets became part of our venacular. Can you say, Fluffer?

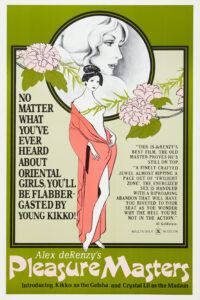

As Hollywood film productions were very public and an honor to work on one, it is easy to identify ownership of films and the many artists associated with their production. With adult films, in particular from 1900s to the early 70s, it is very difficult to find physical records of ownership or creative contributions by artists. Why would anyone in their right mind want to legally copyright contraband; however, when the late 60s came to be, filmmaking became an art form. It did not matter if a film had sexual overtones or content. It was all part of artistic expression and it was not to be censored based on the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Young filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger and Alex de Renzy were bold about their craft. Their artistic pursuits provided them a way to navigate the legal system. This was the beginning of The Golden Age of Porn and paved the way for some amazing films,

When I began developing the Erotic Folk Art of American Cinema exhibition, collecting or preserving adult films and ephemera in the United States was taboo and objects were difficult to access. The only repositories of such materials was The Exodus Trust/The Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality (IASHS) in California, The Kinsey Institute in Indiana and a few archives by actual filmmakers and their distributors. Interestingly, American adult films and their ephemera were trending in the United Kingdom and Europe. These countries had become a hot market to collect vintage Americana. It was during my research at IASHS that I met Tony Nourmand of Reel Art Press. He was in the process of creating a book entitled, X-Rated: Adult Movie Posters of the 60s and 70s. His book project was impressive as no one had previously documented these posters for their artistic value. Nourmand published his elegant book that has since expanded into many editions. I highly recommend his book for discerning collectors of adult movie posters.

When I began developing the Erotic Folk Art of American Cinema exhibition, collecting or preserving adult films and ephemera in the United States was taboo and objects were difficult to access. The only repositories of such materials was The Exodus Trust/The Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality (IASHS) in California, The Kinsey Institute in Indiana and a few archives by actual filmmakers and their distributors. Interestingly, American adult films and their ephemera were trending in the United Kingdom and Europe. These countries had become a hot market to collect vintage Americana. It was during my research at IASHS that I met Tony Nourmand of Reel Art Press. He was in the process of creating a book entitled, X-Rated: Adult Movie Posters of the 60s and 70s. His book project was impressive as no one had previously documented these posters for their artistic value. Nourmand published his elegant book that has since expanded into many editions. I highly recommend his book for discerning collectors of adult movie posters.

At this time, I also had the good fortune to meet Ashley West of New York City. They were in the process of creating The Rialto Report: Documentary Archives for Adult Films. West was documenting the stories of actors, directors and film producers of New York’s sex industry in the early 70s. Because of West’s diligent pursuit of knowledge, they were asked to provide historical facts and information for the HBO’s series, The Duece, starring Maggie Gyllenhaal and James Franco. The Rialto Report is pure platinum and I believe their archives should become mandatory study for higher education institutions for all social sciences. For collectors of adult movie posters, they are an incredible source of information as well.

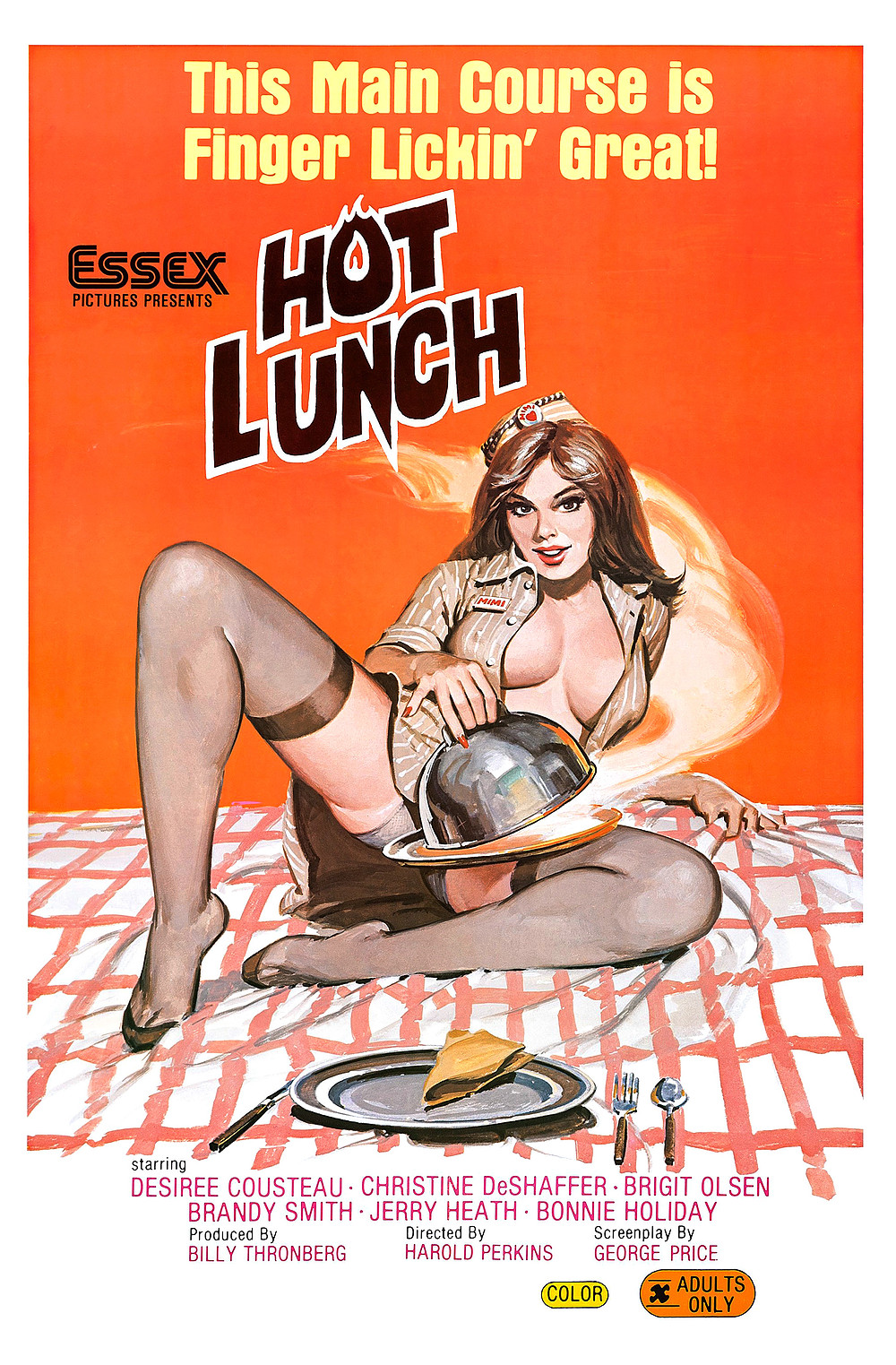

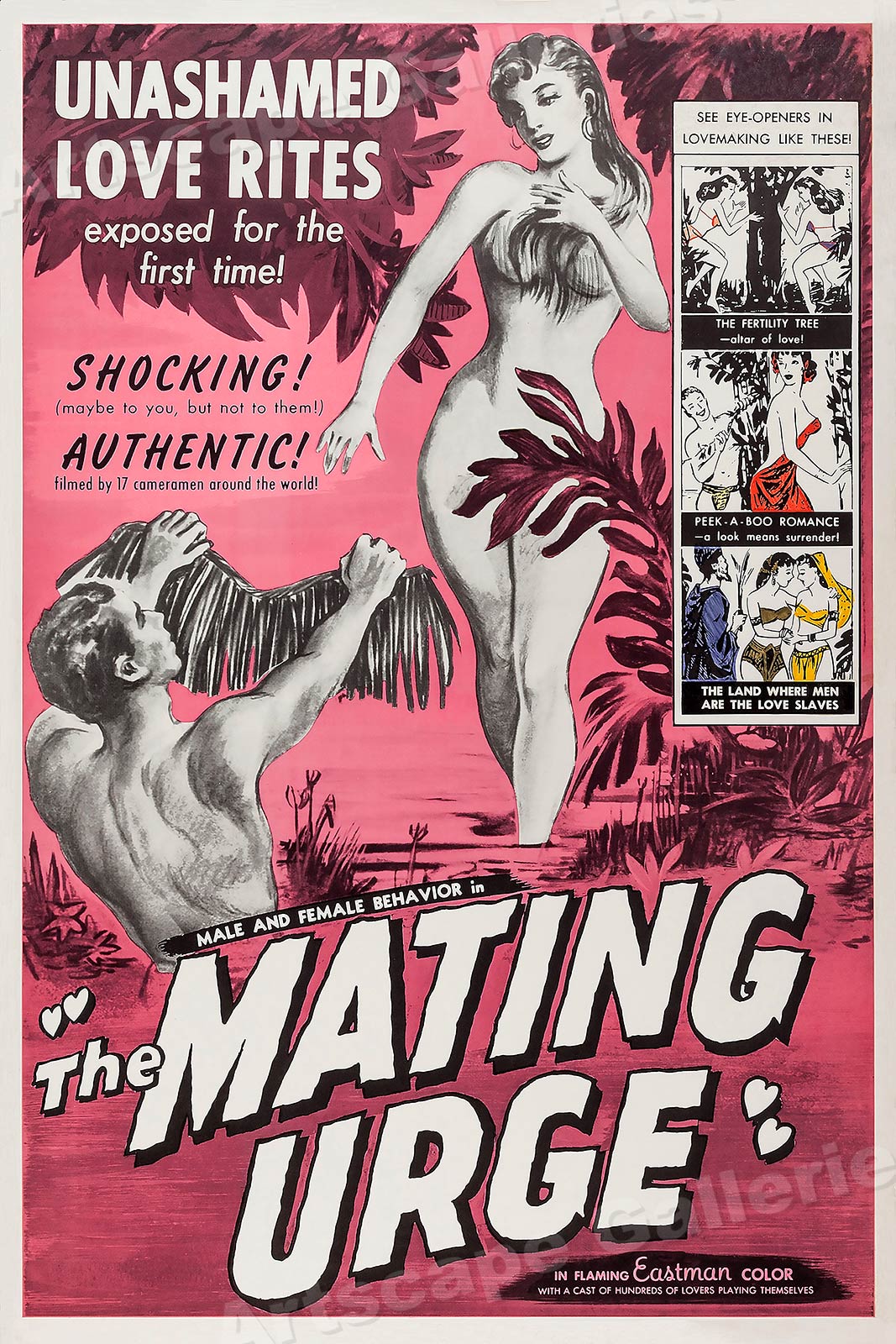

If we look back before the age of the Internet, movie posters were vital to the success of a film. As with mainstream films such as Metropolis, Casablanca, or Star Wars, posters were designed to peak the curiosity of patrons and cultivate the desire to experience a film resulting in ticket sales. Adult movie posters were no different; however, they were designed to bridge the gap of respectable advertising while engaging the sexual fantasies of the average American male. So how do you lure patrons into an adult movie theater without offending the upstanding citizen who might be walking past that adult theater?

If we look back before the age of the Internet, movie posters were vital to the success of a film. As with mainstream films such as Metropolis, Casablanca, or Star Wars, posters were designed to peak the curiosity of patrons and cultivate the desire to experience a film resulting in ticket sales. Adult movie posters were no different; however, they were designed to bridge the gap of respectable advertising while engaging the sexual fantasies of the average American male. So how do you lure patrons into an adult movie theater without offending the upstanding citizen who might be walking past that adult theater?

Posters were gloriously clever with their tongue-and-cheek illustrations and sassy wording. Limits were indeed pushed; yet, looking back at what was considered scandalous then is so very sweet now. What I love about these posters is the fact that they reflect the era in which they were made: fashion, politics, social norms and lifestyles. Prior to 1975, most posters were primarily illustrative. After 1975, photography was primarily utilized to better market the films. Adult movie stars, directors and producers had become household names and the films themselves had become chic. When Alex de Renzy was featured on the cover of Time Magazine and the New York Times called him named him “the Cecil B. De Mille of erotic film”… the adult film industry transformed into a major film industry player, as well as entered the realm of contemporary art. The most celebrated and controversial film of the era was Caligula starring Helen Mirren, Malcom McDowell and Peter O’Toole. In 1979, with a budget of 17.5 million, the film blurred the distinct lines between Hollywood and the adult industry. The film was produced by Bob Guccione, the publisher of Penthouse, and it was his vision to create a historically accurate account of Rome’s infamous Caesar.

Prior to creating the Erotic Folk Art of American Cinema exhibition, as well as the public awareness generated by Nourmand and West, the fate of many adult movie posters in the United States were destined for the garbage dump. People simply did not see their value. The fragile, pin-holed, folded-up posters from a by-gone era were not preserved correctly and deemed discarded junk. As locating master prints of 8mm, 16mm and 35mm film reels proved to be difficult. Finding the space and equipment to store, restore or convert master prints was even more difficult. The cost to conserve these films was exorbitant. Ultimately, adult movie posters became the quintessential representation of American adult cinema. Thankfully, reservoirs of collectible posters have emerged while master film prints have practically vanished. In this new millennium, I am happy to state that trends reflect that what was once passé or too scandalous to covet are now treasured once more. Auction houses such as Christie‘s and Sotheby’s are brining new awareness and value to these wonderful gems. Accredited universities around the world are now preserving these precious one sheets for academic study.

Prior to creating the Erotic Folk Art of American Cinema exhibition, as well as the public awareness generated by Nourmand and West, the fate of many adult movie posters in the United States were destined for the garbage dump. People simply did not see their value. The fragile, pin-holed, folded-up posters from a by-gone era were not preserved correctly and deemed discarded junk. As locating master prints of 8mm, 16mm and 35mm film reels proved to be difficult. Finding the space and equipment to store, restore or convert master prints was even more difficult. The cost to conserve these films was exorbitant. Ultimately, adult movie posters became the quintessential representation of American adult cinema. Thankfully, reservoirs of collectible posters have emerged while master film prints have practically vanished. In this new millennium, I am happy to state that trends reflect that what was once passé or too scandalous to covet are now treasured once more. Auction houses such as Christie‘s and Sotheby’s are brining new awareness and value to these wonderful gems. Accredited universities around the world are now preserving these precious one sheets for academic study.

The names of the artists who designed these posters are nonexistent. The production of designing a poster was the last and final element to producing a film for distribution. It was simply a marketing tool and no one thought twice about artistic value. The goal was to lure people into buying a ticket to watch a flick in the theater. And again, unlike a Hollywood motion picture, it is difficult to find business records associated with the production of adult films. Despite their magnificent illustrations and exquisite layouts, the artists who created adult movie posters chose to remain anonymous. They did not want their names associated with a pornographic film as they feared social or financial backlash. A respectable member of society would not have anything to do with a porno! Thank goodness times have changed in our modern era that artists take pride in their work regardless if their work is created for mainstream or adult films.

I have been fortunate to appraise and peruse the film production records of Alex DeRenzy, Harry Mohney and Larry Flynt. Each of these filmmakers had extensive files to review, but again the artists who created their posters were seldom found. I was told that de Renzy created his own posters. Larry Flynt kept meticulous records of everyone who worked on his projects. As for Mohney, his film production company was so big that the creation of posters simply fell under his marketing department that was ultimately directed by his vision. From what I have been told and what I have seen, everyone who worked on an adult movie during The Golden Age was paid handsomely. I do wonder how lucrative it was for people to produce adult films in the those early days. It had to have been well; otherwise, we would not be where we are today.

I have been fortunate to appraise and peruse the film production records of Alex DeRenzy, Harry Mohney and Larry Flynt. Each of these filmmakers had extensive files to review, but again the artists who created their posters were seldom found. I was told that de Renzy created his own posters. Larry Flynt kept meticulous records of everyone who worked on his projects. As for Mohney, his film production company was so big that the creation of posters simply fell under his marketing department that was ultimately directed by his vision. From what I have been told and what I have seen, everyone who worked on an adult movie during The Golden Age was paid handsomely. I do wonder how lucrative it was for people to produce adult films in the those early days. It had to have been well; otherwise, we would not be where we are today.

American films have always inspired other film industries around the world. This particular genre of American cinema is no exception. When one takes the time to appreciate these posters as stand as distinct works of art, you cannot not be mesmerized by their beauty and intellect.

Viva Erotic American Folk Art!